Between Harz, Heath and Weser Jewish life in central Lower Saxony_ Hameln

Hameln_ city

The “Pied Piper Town” of Hamelin emerged around 1200 at a ford on the Weser River at the intersection of several roads. In the medieval trading town, Jews were mentioned in documents for the first time in 1277, and by the middle of the 14th century their share of the town’s population had grown. However, during the plague period around 1350, their number decreased. In contrast, the authorities in the 16th century seemed to be rather friendly to them; in the Reformation period (1535) they intervened against taunts of Jews. Around 1650 the Hamburg woman Glikl bas Judah Leib was married off to Hamelin at the age of thirteen – as “Glückel of Hamelin” she brought it to fame as an autobiographer. The community had its greatest expansion towards the end of the 19th century after the legal equality of Jews. However, on the night of the pogroms in 1938, the synagogue here also burned down, and more than 100 Jews became victims of the Holocaust. Today, two Jewish communities exist again in the city.

Hameln in detail

In 1277 Jews in Hameln were mentioned in writing for the first time – the sovereign ceded their protective rights to the town. In the first half of the 14th century, they temporarily made up about 5 percent of Hameln’s population. As early as 1341, there is evidence of a synagogue referred to as “dere stad scole”. The sources are silent as to whether in the plague years 1349/50 the Hamelin Jews, unlike their religious sisters and brothers in Braunschweig, Duderstadt, Göttingen, Hildesheim and other towns in present-day Lower Saxony, were spared anti-Semitic murder and terror. But their numbers declined permanently.

Overall, the situation of Hameln’s Jews in the High Middle Ages and the early modern period seems to have been tolerable in comparison with other towns. In the Reformation period, for example, the town council intervened against anti-Jewish amusements at festivals, such as throwing oneself up on cloths. In 1570, a Christian had to pay a fine for “violence against Jews.” And when the Protestant sovereign had all Jews expelled in 1553, the Hamelin council at first refused to obey. One of the known Jewish inhabitants was Joseph Hameln (1597-1677) as the father-in-law of “Glückel von Hameln” – actually her name is deceptive, because she neither came from Hameln nor lived here for a long time. Around 1650, Glikl bas Judah Leib, a thirteen-year-old from Hamburg, was married to Joseph’s son Chaim in Hamelin. However, the couple left the town for Hamburg after only one year. Glikl gave birth to 14 children, was an extremely successful merchant, and was the first woman in Germany to write a significant autobiography, which has been preserved.

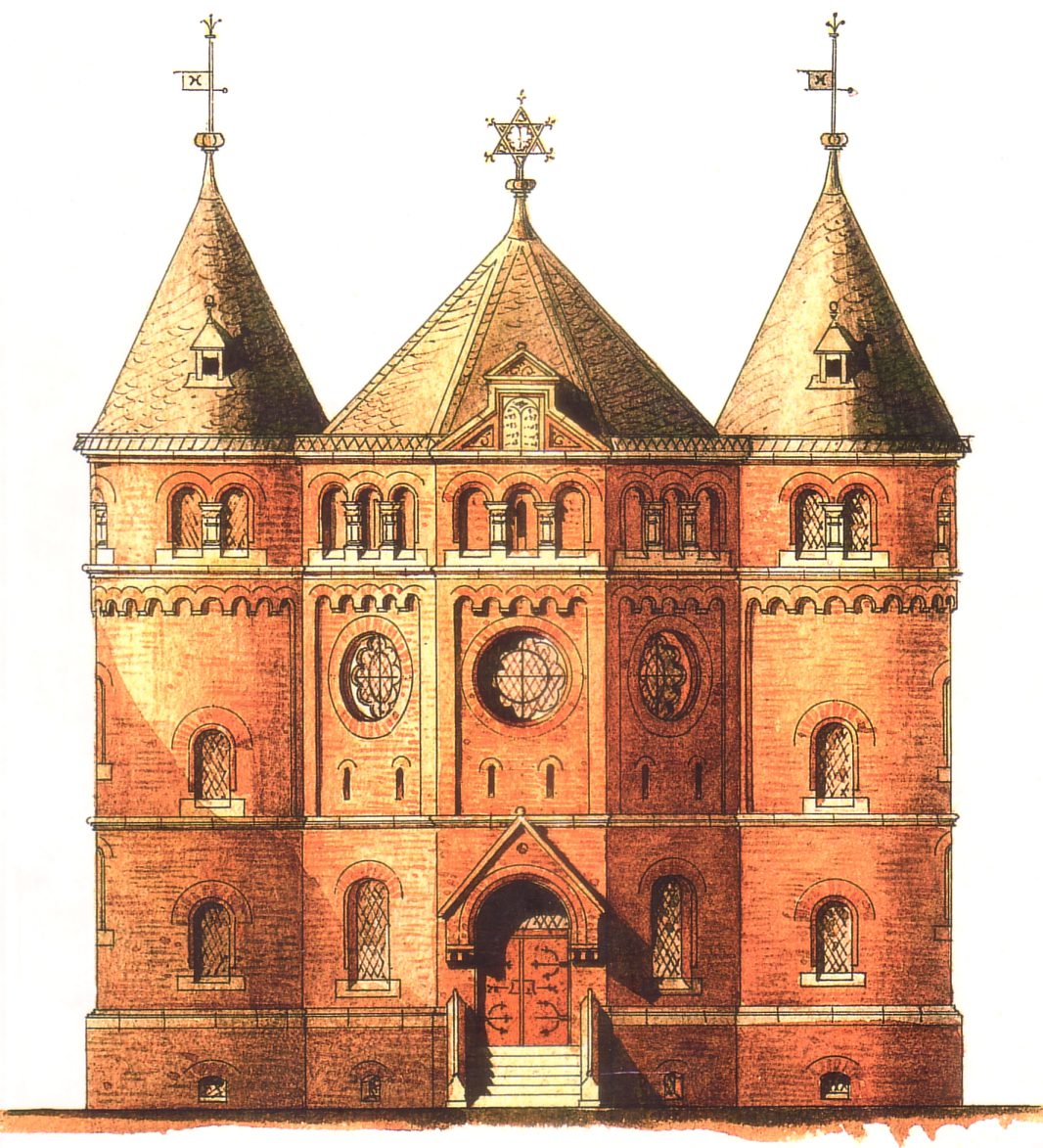

The life of the Jews in Hameln improved only gradually in the second half of the 19th century. After the annexation of the Kingdom of Hanover by Prussia in 1866 and the subsequent founding of the German Reich, they achieved legal equality and took advantage of this for professional and social advancement. A pull from the countryside to the cities also caused the number of Jewish residents in Hameln to increase; it reached its peak shortly after 1900 with 237 community members. The synagogue had been located in a room of the house at Alte Marktstraße 12 since 1776 and had long since become too small; a building fund of the community and donations made it possible to build a new representative synagogue in the Romanesque style according to the design of the well-known Jewish architect Edwin Oppler from Hanover. But the building, inaugurated in 1879, became the target of anti-Semitic attacks as early as 1883 – a prelude only.

Most of Hameln’s Jewish families at the beginning of the 20th century belonged to the middle class. Predominant occupations were independent retail trade, primarily with clothing, traditionally also livestock and horse trade as well as land trade. Two department stores in the town also had a Jewish owner.

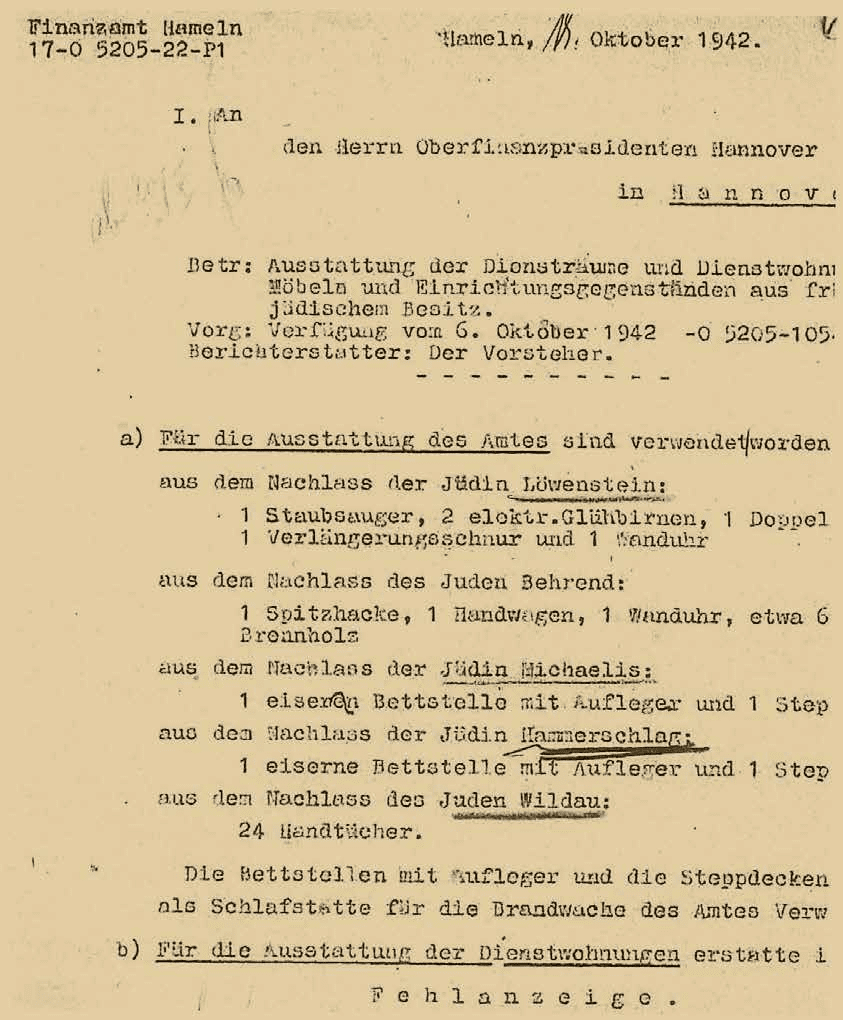

Even before the official boycott day on April 1, 1933, radical anti-Jewish actions began in Hamelin: Uniformed SA men barred shopping in stores, and an arson attack was made on the synagogue. On the boycott day itself, a large advertisement in the local “Deister-Weser-Zeitung” listed a total of 29 Jewish businessmen, doctors and lawyers with their names and addresses. Two years later, a good two-thirds of the companies, stores and practices mentioned had been closed or sold, and the number of Jewish inhabitants had been reduced by about one-third, mainly through migration to the anonymity of the big cities and emigration. The pogrom night of November 9/10, 1938, hit Hameln’s Jewish community hard. The synagogue burned down, the desecrated cemetery was littered with tombstones knocked over or smashed with pickaxes. Ten men were deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp; of the eight survivors, only three managed to leave the country.

Already in October 1939, and thus earlier than in other cities, community members were ghettoized in “Jewish houses”. The final extermination of Hameln’s Jewish community began with the first deportation of March 1942, leaving only a few Jews in “mixed marriages” behind. More than 100 Jews became victims of the Holocaust. None of the expellees returned to Hameln.

The British occupation forces and the Jewish community of Hanover urged the city administration to repair the Jewish cemetery. In 1946, the municipality agreed to do so. But it remained an imperfect reconstruction, many gravestones were smashed or had disappeared. It was not until the 1990s that two new communities were founded in quick succession: The Jewish Community of Hameln e.V. is a member of the Landesverband der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden von Niedersachsen e.V., and the Jewish Reform Community of Hameln (JHG) belongs to the Union of Progressive Jews in Germany. Members of both communities are mostly immigrants of Jewish faith from the former Soviet Union.