Between Harz, Heath and Weser Jewish life in central Lower Saxony_ Hannover

Hannover_ city

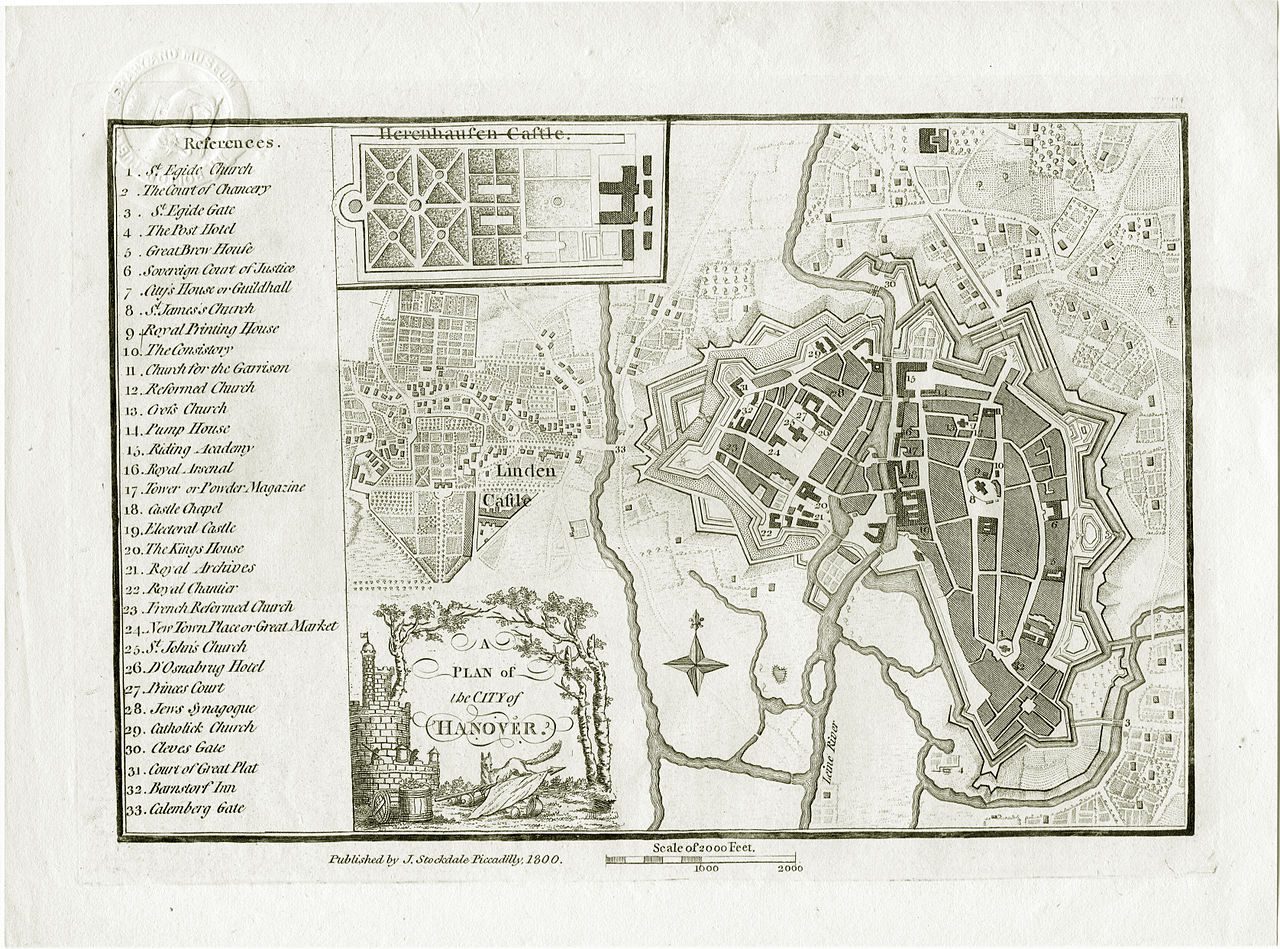

Jews have lived in Hanover for over 700 years – until they were legally equalized as a minority in an often hostile Christian majority society. In 1588, the Protestant council expelled them from the old town. Until the 19th century, Jews could only live as merchants and lenders in the Guelph New Town – “Schutzjuden” under special law and special taxes. A first synagogue was also built here.

After its equalization, the number of Jewish inhabitants increased to almost two percent of the city’s population, mainly due to an influx from the countryside. Jewish entrepreneurs and inventors made a decisive contribution to Hannover’s industrial development. Before the beginning of Nazi rule, Hanover’s Jewish community was the tenth largest in Germany. It was wiped out – a memorial on the central Opernplatz lists the names of those murdered. After the liberation by the Allies, two new communities were established in parallel; today Hanover has four Jewish communities.

Hannover in detail

Jews have lived in Hannover for over 700 years. They are first mentioned in a document of the year 1303 with the admonition that “no one offends the Jews by words or deeds”. In this period the Hanoverian pledge register mentions Jewish inhabitants as money lenders. The plague of 1350 seems to have spurred hostility towards the Jews here as well; in any case, the protective clause in favor of the Jews is subsequently missing. In 1375 the city acquired the “Jewish privilege” from the Guelph sovereign and could now decide on their settlement and the amount of the “protection money” to be paid. Around 1500, there were probably more Jews living in the new town, which was subject to the sovereign, than in the old town under the rule of the town council. Around 1550 they acquired a sand hill outside the city as a burial ground, the Old Jewish Cemetery in the North City, which still exists today. Its oldest surviving gravestone dates from 1654.

The troubled Reformation period supported new hostility. Towards the end of the 16th century, Hanover’s Protestant clergy preached against blasphemy and usury by Jews, the Old Town Council worsened their business opportunities, and the duke finally expelled all Jewish subjects from his land. For the (old) city of Hanover this meant that it was “free of Jews” from 1588 until the 19th century. Jewish life now essentially took place in the princely new town, especially after Hanover’s elevation to the status of a royal seat in 1636 led to new fields of business, which were often transferred to Jews. Leffmann Behrens became known as the court and chamber agent of the Hanoverian Guelph dukes, but equally as the builder of the synagogue in 1704 on a privately purchased plot of land in the Neustadt.

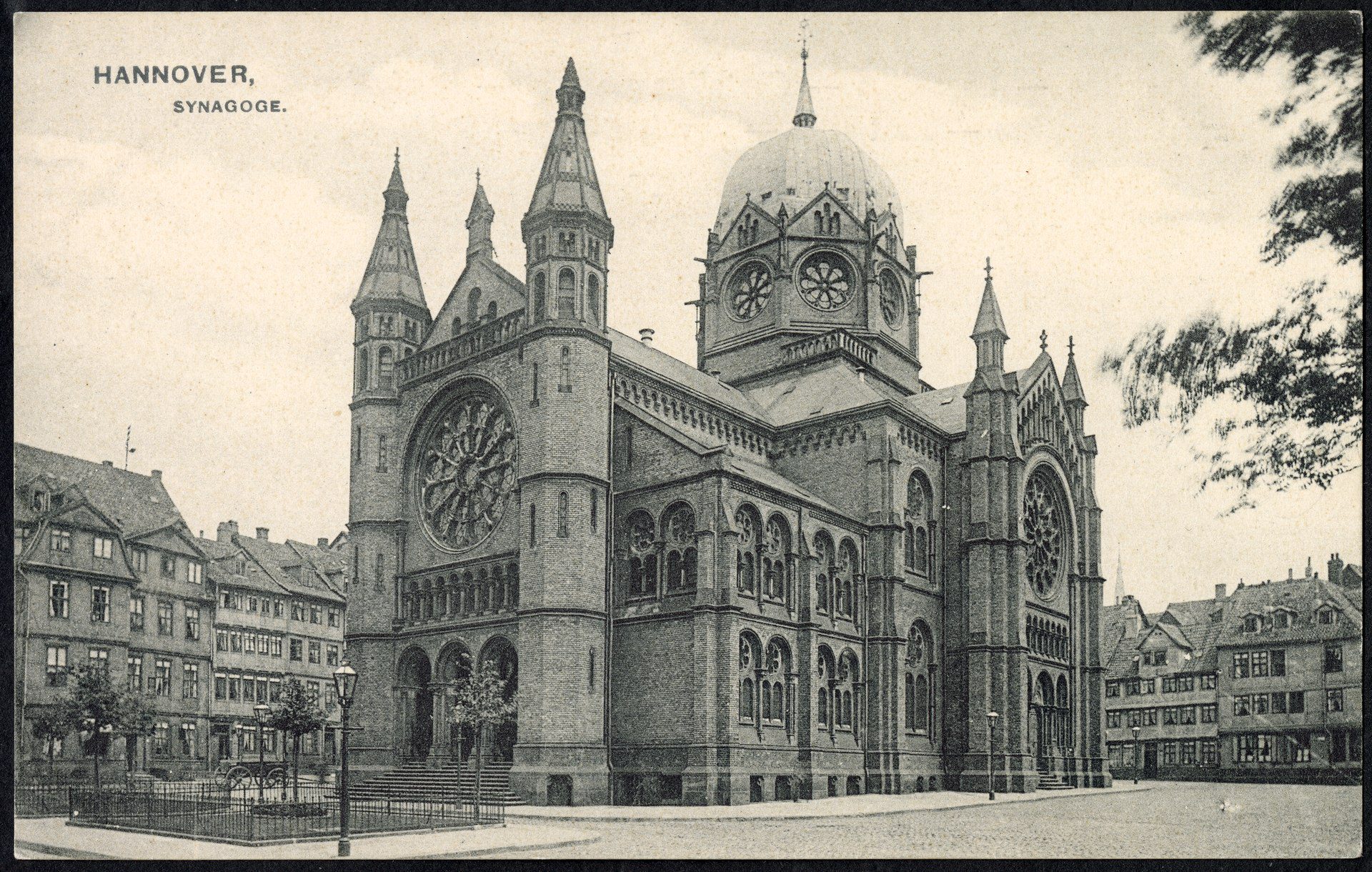

During the Napoleonic occupation (1806-1814), Jews enjoyed legal equality for the first time – which was immediately revoked in the course of the Restoration and the Kingdom of Hanover that was then created. They gained full civil rights and freedom of trade after annexation to Prussia in 1866, and Hanover’s community grew by leaps and bounds to become one of the ten major German communities, with Jewish bankers, entrepreneurs and inventors making a decisive contribution to Hanover’s development into one of Germany’s largest industrial centers. For example, the role of Jewish private banks in the founding of Hannoversche Maschinenbau AG (Hanomag), Continental AG or Mechanische Weberei as the largest manufacturer of its kind on the European continent should be mentioned. There are inventors such as the Berliner brothers (Deutsche Grammophon-Gesellschaft), Ferdinand Sichel (Sichel-Leim), entrepreneurs such as the long-time chairman of Continental AG, Siegmund Seligmann, architects such as Edwin Oppler, who designed the great synagogues of Hameln, Breslau and Hanover, and benefactors such as Moritz Simon (Israelitische Gartenbauschule Ahlem near Hanover).

But success creates enemies. Already in the German Empire, a new, now racially based anti-Semitism developed, which did not stop at Hanover. It became more radical after the lost First World War and in the political struggles of the democratic Weimar Republic. In 1927, the synagogue was smeared with swastikas and the call “Beat the Jews to death,” and in 1928 the National Socialist Party began a campaign against Jewish department stores as alleged “robbery institutions.” But this was only the beginning.

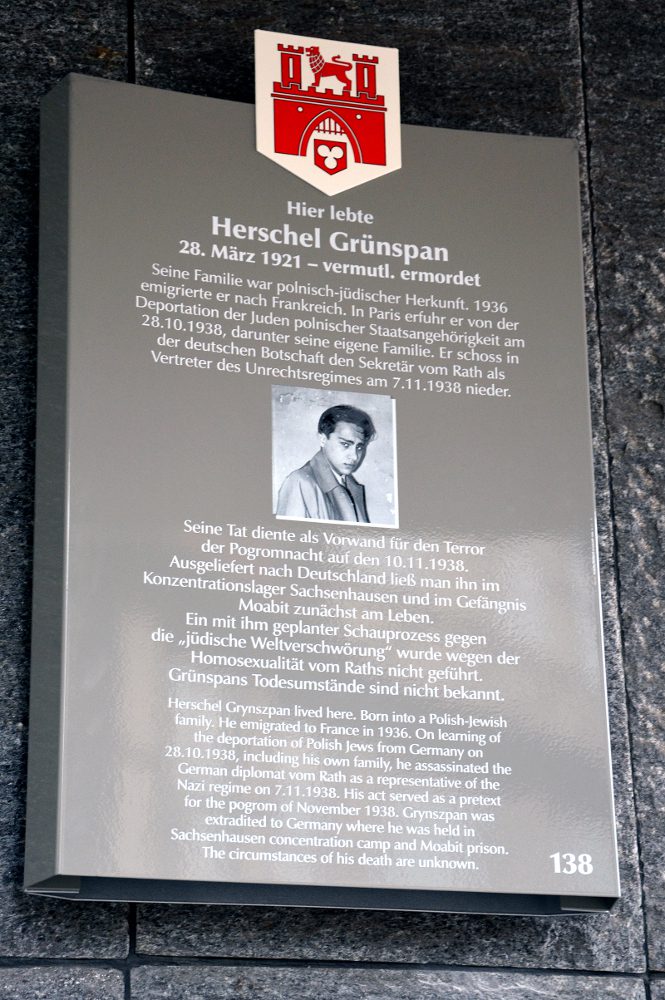

On the night of November 9-10, 1938, anti-Jewish measures in Hanover also radicalized into an orgy of violence: the New Synagogue was burned, Jewish stores and homes were destroyed and robbed, and some 70 men were transported to the Buchenwald concentration camp. In 1939, the Jewish population of the city had halved to about 2300 mostly elderly people; by 1941, their numbers had dwindled to about 1600 Jews as they continued to flee. Beginning with December 1941, seven deportations led to the extermination camps of Eastern Europe.

When Allied troops moved in on April 10, 1945, there were barely 100 Jews left living in Hanover – outside the camps – mostly in intermarriages with Christians. But soon after the liberation, two new communities emerged. The Jewish DP community in Hanover was the largest in the British zone after Bergen-Belsen, with over 1200 members at times. It organized itself as a “Jewish Committee” separate from the newly founded German Jewish community, after the emigration of its mostly Eastern European members it merged with it in 1955. In 1963 the newly built synagogue was occupied.

Today Hannover has four Jewish communities. In addition to the Jewish (traditional) community, the Liberal Jewish Community was founded in 1995 and opened its synagogue “Etz Chaim” in the former Gustav Adolf Church in January 2009. Sephardic-Buchar Jews have existed in Lower Saxony’s state capital since around 1997. In 2013, the community moved into its own blue synagogue – also a repurposed Protestant church. The Hasidic Orthodox movement Chabad Lubavitch has an even shorter history in Hanover, but since 2021 has also had its own synagogue – integrated into a historic train station building.